As a child, I distinctly remember noticing a strange scar on my mother’s upper arm, near her shoulder. It looked like a ring of small indents surrounding a larger one. For some reason, it fascinated me—but like many childhood curiosities, I eventually forgot about it. Years later, while helping an elderly woman off a train, I noticed the exact same scar in the same spot on her arm. My curiosity returned instantly, but there was no time to ask her about it. Instead, I called my mother.

She laughed and reminded me she had explained it before: the scar came from the smallpox vaccine. Smallpox was once a devastating viral disease that caused fever, severe rashes, and often death. During the 20th century, it killed roughly three out of every ten people who caught it, according to the CDC.

Thanks to widespread vaccination, smallpox was declared eradicated in the United States in 1952, and routine vaccinations stopped in 1972. Before then, nearly all children were vaccinated—and the vaccine left a permanent mark. That scar became a visible sign that someone had been protected against smallpox.

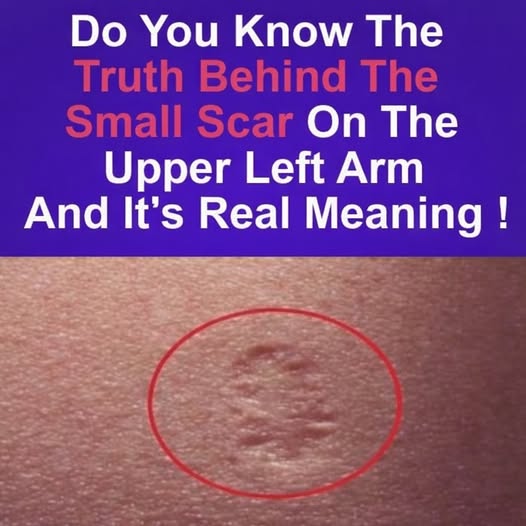

Unlike modern vaccines, the smallpox vaccine was administered using a two-pronged needle that made multiple punctures in the skin. This caused a localized reaction: bumps formed, turned into fluid-filled blisters, then scabbed over as the skin healed. The result was the familiar round, indented scar many older adults still have today. That’s the scar my mother carries—and why so many people of her generation share the same mark of history.